|

It has been a busy couple of weeks for me the joint exhibition at Turner Sims Southampton with Kezia Davies has been set up and now open to the public. Also I have handed in my final major project for the degree course and I am awaiting the results I am hoping I do well and plan to go on to study for an M.A in fine art. I am feeling very excited as the private view for the degree show opens tomorrow, although this is also a sad day as the three years of studying for the degree is over and I will miss my fellow students dearly. Below a couple of photos of the space during set up and Marion from second year helping get the space ready she was brilliant and helped out a lot during the process of setting up.  I arrived early for the degree show to help set up the bars there was a buzz in the served with a slice of trepidation.As it happened the nerves were for nothing as everything came together and people started to arrive. I think the students who helped from lower year had a role in the success of the show and should be acknowledged.There were plenty of visitors and positive comments the shop was also a big hit thanks to everyone who helped with the shop. The enthusiastic way the visitors talked about the art in the show spoke volumes to me the other artists all seemed to enjoy themselves and were happy about the success of the show. Exhibiting Artist Sharon Harvey Exhibiting Artist Elaine Ford little men(kogs) at the end of the jetty by exhibiting artist Edward Frampton.

1 Comment

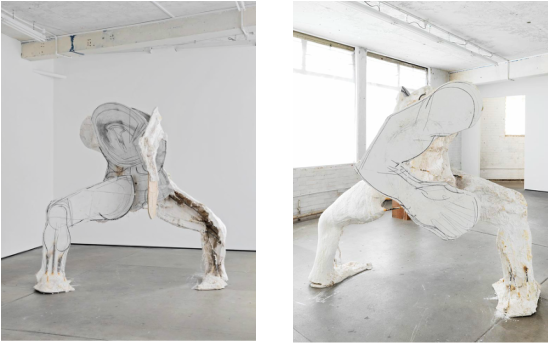

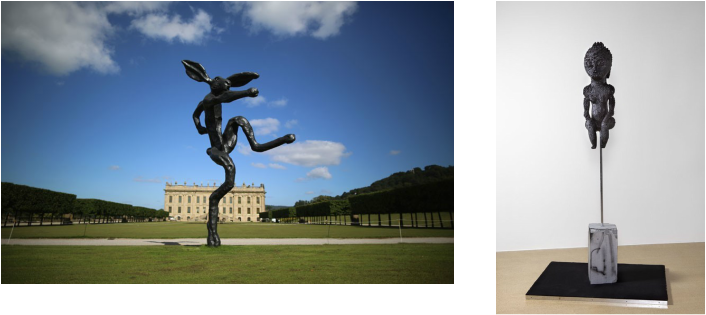

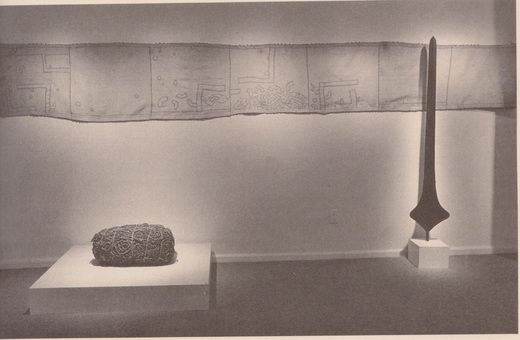

In my work I explore figurative and archaeological forms, also the link between our primal nature, the environment, the natural world and the world in which we live today. This is often manifested in our need for green spaces and a yearning to get back to nature and connect with our past. These green spaces are what inspire my artwork. I often visit Dartmoor and whilst out walking in this beautiful, wide open, heather clad landscape, I often come across prehistoric settlements, stone circles, cists and stone rows as well as natural formations such as Hound Tor. It was the stone circles that really captured my interest: the size of these objects makes them an imposing presence on the landscape. Being surrounded by the stones, one can sense the importance of them to Neolithic peoples and the rituals surrounding these objects. It was because of this relationship between stone circles and the landscape and ritualistic significance that I began using the stones’ rectangular, if somewhat irregular, form as a central theme in the work.  I started making the sculptures by using materials that are natural such as wood, plaster and scrim to create the work. I was making something artificial out of something from the natural world. Although the materials that were chosen to create these objects was clearly not stone it was important that that materials used were from the landscape to maintain a connection with the earth and natural world as well as a temporal one. In Andrew Jones’ book, Memory and material culture, he refers to Alfred Gell (1998, 233-42) saying “Gell is concerned with the temporal position of artworks in networks of causal relations. He draws on Husserl's model of time consciousness as a means of examining how objects are positioned in time. For Husserl, time moves forward as a series of temporal events, but each of these events encapsulates elements of past events (retentions) and embodies components of future events (protentions). Gell employs this concept to analyse the artistic oeuvre of both individuals and collective groups. Artworks are positioned in time as a series of 'events' embodied in material form by the artwork itself. By drawing on pre-existing artworks the artist embodies, in the new artwork, elements of what has gone before. By materialising the artwork in physical form, the artist projects his or her intentions forward in time in the form of the artwork. What Gell is concerned to relate here is the extent to which artworks can be treated as indexes of human agency and how, as indexes, artworks subsequently affect human action”. Monuments are good examples of this as often what you will find out is that that some monuments have changed over a period of time until they are finally abandoned but traces of the past are encapsulated within them. Eventually they become important again through man’s intervention and need to connect to the past. In art work by Thomas Houseargo I like the way the figures that he makes look like they might be idols that belong to a primitive tribe. Similarly, his masks could have the same origins and the figures also could be from Greek mythology for example the cyclops. The materials he uses to construct the figures are similar to what I use when making my work. Houseargo’s work often seems imperfect with rebar showing through the sculpture and cracked plaster. This is intentional and gives the work a raw feel. I like this about his work and my work often has rough edges all cracked plaster I think this also communicates the primal nature of the work and for me a need to uncover something concealed or out of reach. Maurice Blanchot when referring to the Myth of Orpheus and Eurydice (a woman of great beauty) relates the story to art. Orpheus is confronted by his love Eurydice’s death after she was fleeing from a shepherd called Aristaeus and his unwanted advances was bitten by a snake and died shortly afterwards. Saddened by this turn of events Orpheus gains entry to the underworld. By playing his lyre he obtains the permission of Hades but Hades sets one condition, that when Orpheus leads Eurydice out of the underworld he cannot gaze upon her he can only look at her in full light of day. However, such is the temptation to gaze upon her in the darkness he turns around to gaze at her. The moment he witnesses this, she is consumed by the darkness and he has lost her once more. The Myth from the perspective of art is referring to the perfect moment when the artwork is conceived, the point of origin, but as soon as the artist shares this work though artistic expression, through music, painting, the work itself becomes subjective and is lost and the artist’s desire for that perfect moment is what drives them to keep creating. An infinite search for a moment which can never be reached.  Thomas Houseargo Figure 1 and 2 This is an important point to make, as an artist I am continually reinventing my work and will use old artworks as a platform for doing so. Without this starting point my work would not be able to travel forward and so my work always retains a relationship with the past and my past work has also been inspired by the past. I have recently started morphing my old sculptures into new work. I thought this would be interesting and the past and the future seem to merge together within the confines of the work. I have even begun to crack the plaster on some sculptures, which unveils the process of making, exposing the way in which the work was made feels akin to an archaeological dig. I have also left another unfinished. This allows me to explore possibilities of temporality through the work and the process of making though time constructs. Every artwork that I create seems to embody some element or traces of previous artworks within it a memory if you will. As Gell states “without repetition art would lose its memory”. One might argue that this repetition is ritualistic in its construct, unearthing and recreating basic forms and symbols which seem to be inherent within the human psyche and seem to be repeated as artworks the world over. This is referring to a collective unconscious theory of the collective unconscious is an interesting concept Carl Jung thought, that all the attributes of a person’s nature are inherent within us from the moment we are born, and that the metaphysical world that surrounds us as individuals brings us out rather than the environment shaping us. Jung surmised that we are born with a “blueprint” within ourselves, our lives are literally mapped out before us and this will determine how we live our lives and the choices we make. Although our blueprints can be influenced by the numerous archetypes in our lives for example our mother, father, grandparents on so on and also major events. Other archetypes which pertain to the natural world such as the moon, sun, trees and symbols amalgamate and manifest within ones’ psyche and are often expressed artistically through means of stories, paintings and myths. According to Jung, “the term archetype is not meant to denote an inherited idea, but rather an inherited mode of functioning, corresponding to the inborn way in which the chick emerges from the egg, the bird builds its nest, a certain kind of wasp stings the motor ganglion of the caterpillar, and eels find their way to the Bermudas. In other words, it is a ‘pattern of behaviour’. This aspect of the archetype, the purely biological one, is the proper concern of scientific psychology. “According to Shaikat Hossain on Jung he states “The concept of the archetype is the manifestation of the collective unconscious’s psychic content in the form of certain “primordial images.” These images are commonly expressed in much of the world’s mythology and religious scriptures. Some of the more common archetypes include the Great Mother, characterized as being nurturing and strong, as well as the Wise Old Man, who is characterized as being knowledgeable and insightful. These conceptions are innate and have been found to be consistent across many different cultures and religious backgrounds”. Two earlier works of mine relate to death; one the fear of being buried alive which is a fear a lot of people across the world share and the other an ethereal presence such as a god head essentially the father figure is as stated by Jung inherent within the psyche. The third sculpture, to me, represents a bull which, in mythology, gods would take the form of. As in the Zeus and Europa story which makes sense as bulls represent strength and power and the horn of the bull represents virility - procreative vigour. My current work relates to these primordial images or archetypes and are still present within my work although I have recently become interested in power objects. The idea that an object can have such power by channelling a spiritual being’s energy is a weird concept to most western people today but one could argue that a Nkisi object from Africa is no different to the cross when used to cast out demons or marking a baby’s forehead with the sign of the cross using oil in its original it is a sign of possession through baptism. Christ through victory laid his hand on the one being baptised although religion or belief systems are different throughout the world at their core is the belief in connecting with a spiritual entity or energy that is bigger than us as human beings whether it is a god a multitude of gods or Buddha. I recently visited the Horniman Museum in London where they had a number of curiosity’s which included voodoo alters totem poles and other artefacts but it was the African marks and Nikisi objects that I engaged with. It was the Portuguese and the Dutch who landed in the Gold coast of Africa in the 16th and 17th centuries they were the first Europeans to came across power objects which they named "feitico” and later the word fettiso was coined by Portuguese and Dutch merchants which was a word for these objects or artefacts from which is the word "fetish" is derived. According Andrew Jones “For Pels (1998,91) the fetish ‘foregrounds materiality because it is the most aggressive expression of the social life of things. Fetishism is animism with a vengeance. It’s matter strikes back’. It can both subjugate and dominate persons. Pels (1998,94) is quite clear in distinguishing fetishism from animism; whereas animist belief proposes that spirit resides in matter, fetishism posits an assumption of the of matter: objects have spirit and are able to act of their own volition to attract or repel people. These distinctions are important because they help us clarify and reposition our perception of the object world. The key point here is that fetishes concentrate or localise human experience and belief in the power of objects.” Nkisi objects are often referred to as fetish objects. Karl Marx has an opposing view of fetish objects to Pels. according to Andrew jones” Marx employed the concept to describe the relations between people and things in capitalist economics. It occurs in his description of commodities: a commodity becomes a commodity not as a material thing but as an abstract value of exchange. For Marx to fetishize the commodity was to fetishize the abstract exchange value. As Stallybrass (1998,184) points out, for Marx fetishism is not an intellectual or categorical problem, it is the fetishism of commodities that it the problem. What capitalism does is to make a fetish of the invisible and immaterial. This stands in contradistinction to colonial definitions of the fetish, which signified the apparently arbitrary attachment of west Africans to material objects”. It could be argued that Pels had the right approach when trying to categorise the objects as the objects are traded as commodities within African societies and under these condition it is the belief in the objects power that defines it as an object of value when traded but when the object comes into a westerners possession this is because it no longer has value as a power object It could be said that it is then that Marx’s theory plays out as it is no longer an object of power but one of desire for a collector at this point it becomes a commodity. The nkisi figures originate in Congo and Zaïre and gifted with their powers by the medicine man or "nganga” the figures themselves have a hole or holes around the abdomen into which a pouch would have been placed inside the pouch there would have been a number of sacrificial materials which includes items such as clay, blood, plants and mounted with a mirror sometimes placed in small box. These ingredients, called bilongo positioned on the nkisi object at specific periods throughout the lunar cycle and, if its powers are revealed to work, they can be used independently. The objects are sometimes used for the good of the community. These figures are known as nkonde and often used for settling disputes, quite literally hammering out disagreements, an oath or pact. In this way social order is maintained. They can also be used to ward off curses and other means of sorcery simply by placing a nail or blade into the object; each time this is repeated the powers of the object are restored. Whilst researching these objects I became interested in Boli or (Bovine) cow like objects from Bamana, Africa (now Mali) Consisted of a rough cracked surface made up of layers of organic and inorganic material which include blood, honey, animal bones, plants, urine, kola nuts which have been chewed and passed, millet and alcohol and metal under which is a wooden armature, which is covered with cloth. Each layer that is added to the surface are what gives the figure its power and unique patina. These entities play a vital role within Bamana spiritual life. Through repeated offerings, the power of the of the boli object is restored and increased. Boli objects principal role is to amass and control the nyama or the energy or life force which occurs naturally. This is so that the community can profit from it spiritually. Boli have a loose amorphous form The round bulging shape of the object had aesthetic draw; the various layers of materials that seem to breathe life into the object transforming into this object of power because it is non-descript and zoomorphic while other objects with no spiritual significance could be considered anthropomorphic having human like attributes but not having spiritual qualities embedded within or projected onto them as the Boli objects do.  Ritual Object (Boli), Mid-19th/early 20th century Nkisi ritual object “Try as one might, …The object fails to keep its distance, abandons its reserve, overflows…” (Hollier 1992: 17). Ingold expands on this fluidity of materials: “they are relentlessly on the move – flowing, scraping, mixing and mutating. The existence of all living organisms is caught up in this ceaseless respiratory and metabolic interchange between their bodily substances and the fluxes of the medium.” (Ingold 2007: 11). The materials and their interactions within the boli object become free of physical substance and start to decompose, dissolve, crumble , and erode this organic process carries on even after interaction with humans has ceased to exist even without human agency the boli still breathes “like smoke which logs of oak, heat and fire emit; some of a closer and denser texture, like the gossamer coats which at times cicadas doff off at summer, and the film which calves at their birth cast from the surface of their body, as well as the vesture which the slippery serpent puts off among the thorns; for often we see the brambles enriched with their flying spoils, since these cases occur, a thin image likewise must be emitted from things off their surface” (Lucretius in Gell 1998: 105).This process of decay and fluidity where in the object is in a constant state of flux resonates with me and it is something I endeavour to create through the work I make. This does beg the question though of whether the work gets lost in translation because I do not grasp fully the culture from which these objects relate to whether that is African culture or an historical period of time. I cannot possibly factor into my work the significance of monuments or African artefacts to people from those particular cultures I can only convey my relationship to them. In the case of the African power objects this is with a western gaze and post-colonial view point and then the work runs the risk of becoming arbitrary. I think the way this can be avoided is to approach the objects in a similar way to other artist who make similar work to mine like Ed Lipski. On the Alan Koffee Gallery website is stated “Edward Lipski (British, b. 1971) is an artist and sculptor known for successfully expressing uncomfortable places in the human psyche through super-real mannequins as well as cartoonlike figures. His work often has a certain unsettling playfulness to it, distinguishing his particular approach to the grotesque. Lipski has said of his art: “My sculptures are mistakes in the same way language itself is kind of a mistake… language is an approximation, an attempt to describe the world, but an attempt that is doomed to fail”. By combining his conceptual thought process with this pre-linguistic means of conveying imagery, Lipski’s work stands apart from the current generation of young British artists”. That is not to say that artwork of this nature has no validity because it does, going back to the point of Carl Jung’s theory of the collective unconscious and “The concept of the archetype is the manifestation of the collective unconscious’s psychic content in the form of certain “primordial images” and to a certain extent these primordial images are embedded within my work and artists such Ed Lipski. This playful approach to artwork is something that I value working through ideas in this manner is both invigorating and intuitive and I think that comes across in my artwork, also because of my interest in ritual temporality and primordial imagery my work is sometimes unsettling although it is offset by the playful nature of my work. In the 1970s the artist Barry Flanagan began chiselling into chunks of stone what primitive figures and marks which seem to resemble the marks found on standing stones. Tantric Goddess was carved into a large block which was irregular. In 1979 Flanagan happened upon a hare in the window of a butcher's shop, procured the hare and took it back to his house where he made a clay model of it, this was cast then at the foundry he used prior to which was a Spratt's dog-biscuit factory. The outcome of this chance happening the first rendition of was his Leaping Hare, the forerunner of his series of hares which he was prolithic in producing. In his hare Flanagan had found certain attraction being a primal fertility symbol in the ancient religion captured his interest. Other animals were produced by Flanagan but it was the hare that resonated with this primordial symbol with its sexual overtones and connection to the arcane held his and people’s attention over the course of the artists life and these hares were often depicted in a playful way similar to Lipskis artwork although Flanagan’s work is not disturbing in any way.  Ed Lipski Fang (Venus), 2010 Barry Flanagan Nijinski Hare 1989 Bruce Nauman on the other hand whose works often relate to death, sex and violence and parts of the body such as wax heads and hands, are sometimes disturbing and thought provoking. I would say that sometimes these body parts are used to communicate a message to the viewer. Also he has done work that conveyed a spiritual message; the artwork was a neon sign saying “The true artist helps the world by revealing mystic truths." Although his art provokes a response because of its confrontational nature I feel Nauman’s art work tackles themes that are in my work such as death, sex and fear I feel Nauman’s work is tackling fundamental things in everyone’s life and the confrontational in your face nature is something I do not shy away from it could be said that Nauman’s grotesque images that he uses relate to my work. Nauman has also used the casts of the bodies of animals, the casts are based on the ones used in taxidermy. In the work taxidermy carousel which relates to death and confrontations of death in his work I am also tackling similar themes in the fetish boli these objects deal with the same issues but in a different manner the boli has a spirit and is spoken to and is very much present on the other hand the taxiderimed objects in Nauman’s work are void off life, they confront your fears in a grotesque way that is uncomfortable. Similarly, I am considering the use of organic and bodily material during the layering process. I like the raw in your face attitude that exists in Nauman’s work he famously once said “he wanted his art to be as powerful and direct as being hit in the face with a baseball bat”. Ed Lipski has said of his art: “I take the outsider perspective; it was never my concern to align myself with the current art language. I look to the streets; I look at my environment; that’s where my art culture is being formed. I look at raw nature [and] listen to a lot of contemporary music. [The quintessence of now, which I try to put into my works] is a combination of vagueness and particularity. Enjoyment and pleasure that comes out of interfacing things that are disparate in sensation: very technological and very rudimentary, very rough and sophisticated”. It could be said that most artist have seepage from the metaphysical world this cannot be avoided it is what makes our art individual to us and I think as an artist you need to maintain perspective and not get caught up in what others are producing. Trying to relate your work to what is important to oneself but at the same time embrace any naturally occurring crossover or seepage from outside. This is how work sometimes develops in a natural way organic and yet also there is a ritualistic and urgent approach to the way to the way I produce work. Bruce Nauman's carousel 1988  In conclusion the work I am creating and the primordial nature regarding architypes which occur within the depths of the psyche may bring to mind the art carved into ancient stone circles or cave paintings but these images are etched into our very being and still these images come through in contemporary art today. Ed Lipski’s and Barry Flanagan’s artworks bare testament to this. One thing that cannot be inherent to the work I make is a total understanding of what the significance of the objects for a particular culture are. As I have stated, you need to be part of the culture by whom the artefacts were crafted and immersed within in it to fully comprehend an object’s meaning or significance. What I can do is to create a work based on a power object, as this object is not part of the African culture, nor is it part of mine, but it is an object none-the-less an object teetering on the cusp of something and what happens is the metaphysical trappings of my world begin to trickle into the object by material means. This object then becomes an artwork and can begin to communicate and be understood within the contemporary art setting. This temporal nature of my art reflects the materiality in regards to the use of organic substances which are permanently in a state of flux and the constant reinvention of my work leads to the unveiling of what lies beneath the layers through the lithosphere, asthenosphere the part of the mantle that flows just like the inspiration for a new artwork until you finally reach the core where the new idea or work is realised. The whole process of the creation then begins again as the artwork is no longer perfect as it is open to other’s thoughts and the artist returns to the ongoing ritualistic search for the point of origin when the work was conceived. References Anon, (2016). [online] Available at: http:///www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/101653/Boli_Figure_for_the_Kono_Society [Accessed 20 Mar. 2016]. Anon, (2016). [online] Available at: http://www,Alan Koffee Gallery [Accessed 20 Mar. 2016]. Artic.edu. (2016). Ritual Object (Boli) | The Art Institute of Chicago. [online] Available at: http://www.artic.edu/aic/collections/artwork/154023 [Accessed 20 Mar. 2016]. Barry Flanagan. (1987). [Newcastle upon Tyne]: Tyne and Wear Museums Service. Barryflanagan.com. (2016). Home. [online] Available at: http://barryflanagan.com/home/ [Accessed 20 Mar. 2016]. Chevalier, S. (2008). What Does “Materiality” Really Mean? Materiality. Edited by Daniel Miller. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2005. Current Anthropology, 49(1), pp.157-158. Columbia.edu. (2016). Thing Theory 2008 (Skaggs 1). [online] Available at: http://www.columbia.edu/~sf2220/TT2008/web-content/Pages/Katie.html [Accessed 20 Mar. 2016]. Flanagan, B. (1982). Barry Flanagan. London: British Council. Flanagan, B. (1993). Barry Flanagan. Madrid: Sala de Exposiciones de la Fundación "la Caixa". Flanagan, B., Wallis, C., Wilson, A. and Melvin, J. (2011). Barry Flanagan. London: Tate Pub. Google.co.uk. (2016). Google. [online] Available at: https://www.google.co.uk/webhp?source=search_app [Accessed 20 Mar. 2016]. Hollier, D. and Ollman, L. (1992). The Use-Value of the Impossible. October, 60, p.3. Ingold, T. (2007). Materials against materiality. ARD, 14(01), p.1. Jones, A. (2007). Memory and material culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Lippard, L. (1983). Overlay. New York: Pantheon Books. Loggia.com. (2016). Mythography | The Greek Lovers Orpheus and Eurydice in Myth and Art. [online] Available at: http://www.loggia.com/myth/eurydice.html [Accessed 20 Mar. 2016]. Martagnyp.com. (2016). GNYP Edward Lipski. [online] Available at: http://www.martagnyp.com/interviews/edward-lipski [Accessed 20 Mar. 2016]. Nauman, B. and Blume, E. (2010). Bruce Nauman. Cologne: DuMont. Nauman, B., Benezra, N. and Simon, J. (1994). Bruce Nauman. Minneapolis: Walker Art Center. Nelson, R. and Shiff, R. (1996). Critical terms for art history. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. profile, V. (2012). P.E.A.R.: Thomas Houseago. [online] Pearmagazineuk.blogspot.co.uk. Available at: http://pearmagazineuk.blogspot.co.uk/2012/10/thomas-houseago.html [Accessed 20 Mar. 2016]. Searle, A. (2013). Artist Bruce Nauman's carnage-littered carousel will blow your mind. [online] the Guardian. Available at: http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2013/jan/30/bruce-nauman-art-hauser-wirth [Accessed 20 Mar. 2016]. Sherwin, S. (2011). Artist of the week 120: Thomas Houseago. [online] the Guardian. Available at: http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2011/jan/05/artist-week-thomas-houseago [Accessed 20 Mar. 2016]. Telegraph.co.uk. (2009). Barry Flanagan. [online] Available at: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/obituaries/culture-obituaries/art-obituaries/6190100/Barry-Flanagan.html [Accessed 20 Mar. 2016]. Vcu.edu. (2016). Myth of Orpheus and Eurydice. [online] Available at: http://www.vcu.edu/engweb/webtexts/eurydice/eurydicemyth.html [Accessed 20 Mar. 2016]. How cultural Artifacts are viewed when placed in a gallery setting.

To understand about how cultural objects are viewed when placed in a gallery setting we must first look at how the artefacts were acquired and colonism. In 1897 Britain sent a trading expedition to Benin to conduct negotiations with the Oba(king) and his council, however the negotiations did not go according to plan and nine British Naval officers were killed. Britain responded with military force, sending a raiding party to the region. The British were ruthless in the assault on Benin and thousands of native inhabitants lost their lives. Benin was looted by the British and hundreds of artefacts were taken. The soldiers raided the palace and many artworks were removed from there including the Benin bronzes. Despite the name, the Benin bronzes are made from brass. The casting of objects in Africa has been practiced since 10th century but a dwindling supply of metal lead to trade with the Portuguese in the 15th century. Brass came from bracelets called "manillas”, after the Portuguese word for money, which were used as a currency all over West Africa. These bracelets were smelted down and the craftsmen used the metal in the traditional lost wax process of casting. In 1950 the keeper of ethnography at the British Museum, Hermann Braunholtz, told the trustees that thirty of the two hundred and three plaques in the museum’s collection were duplicates and, “surplus to the museum’s requirements”. Braunholtz suggested that ten of the bronzes should be sold for £1,500 because of the lack of the objects in Nigeria. It has since been discovered that assuming the plaques were duplicates was a mistake because they were created as pairs. However, Nigeria at the time was a British colony and plans were being made for a National Museum in Lagos. The selling of the bronzes was thought by curators to be of benefit to everyone with items of cultural significance on display in Nigeria. Benin Bronzes The selling of these items produced income to expand the collection in the ethnography department. The sale of bronzes to Nigeria raised money for the Museum which was used to acquire the Oldman collection of African and American ethnography. The British Museum also exchanged another plaque in 1951 and later in 1953 the British museum sold another to Nigeria. Later, in 1972, William Buller Fagg, the Keeper of the Department of Anthropology at the British Museum (1969–1974), arranged an exchange with Robin Lehman. The exchange resulted in the British Museum swapping two Benin Bronze plaques for a two bronze horsemen from Lehman’s collection. This proved beneficial as the plaques were valued at £4,000-5,000 and the horsemen at £8,000-10,000. The remaining Benin Bronzes have mostly remained in Britain since. The British Museum and The Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford, house a collection the Bronzes. Since world war II the British Museum has sold some of the bronzes to Nigeria for less than £100. Recently exceptional examples have been sold for as much as £100,000. The British Museum now regret this decision to sell the bronzes. There have been questions and rumours about the whereabouts of some of the bronzes in Nigeria. Professor Frank Willett, who was a curator in Nigeria, grudgingly argued against the return of Nigerian artefacts stating that: "It is indeed depressing that having spent the last forty years trying to demonstrate that the peoples of Nigeria have a history and an artistic heritage of which they can be proud, to find that those who now hold the roles we once did are not only not taking care of their heritage, but are exploiting this irreplaceable material by allowing its illicit export to dealers and collectors in the West.” He also stated "I have been keeping an eye on the art market and attempting to arrange for the return of pieces stolen from Nigerian museums ever since I left the paid service of the Nigerian Government in 1963, yet here I am recommending that objects should not be returned.” The way artworks of Africa and other colonies have been acquired and displayed in Museums and Galleries is now, more than ever, under scrutiny. Curators are aware of this and acknowledge colonism and the cultural history of the objects when exhibiting the artefacts. Susan Vogel has held the position of curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and also Founded Art/Artifact: African Art in Anthropology Collections. Her exhibition at the Centre for African Art in New York addresses this issue. In the exhibition art from Africa is presented in three rooms; the first of which makes reference to the way the objects are displayed in exhibitions by artists such as Picasso, Braque and Brancusi who displayed artwork with African art. Although Vogel’s exhibition only displays African artwork, the formal qualities of the artworks and their presentation draws attention to this reference. Vogel’s use of utilitarian objects and the fact there is limited information displayed; just the object’s name, for example, “Net, Zande people, Zaire”. Also the way in which the Kuba woman’s wrapper is displayed like a tapestry on the wall. The form of the metal currency which is in the shape of spear head is similar to modern art works; the smooth clean lines the object has are visually appealing. This currency was used until the middle of the 20th Century and has no practical use as a spearhead. These items ranged from nine and a half inches to fifty-six inches. These objects relate to the Portuguese bracelets that were also used as currency although African people were using these objects as currency a long time before the Portuguese arrived on the African continent. The other item was a Zande hunting net used for hunting animals. This was displayed on a platform with light projected onto it. The way the light was used was clever, it seemed to elevate this utilitarian object into a thing of beauty and indeed Vogel’s chicanery worked, she received inquiries as to where someone might procure such a wonderful net. The second room was labelled The Original African Context and had an unedited and untranslated video by Ernie Wolfe showing the consecration of a Mijikenda memorial post which took place in a village. The label affirming that only the original audience could have the genuine experience and any other experience was capricious rather than having any reason or authenticity. Similar posts appeared throughout the exhibition. The label could relate to the sometimes staged African ceremonies that are experienced by tourists and one would argue that you cannot truly experience this even if you are there because you have little knowledge of their traditions, history or culture. The third room was a reconstructed Hamptons curiosity room of 1905. This room had, according to Vogel “A furniture style and teaching purpose represented the cutting edge for its day.” The objects in display cases were on and against the walls with a table and chairs. Vogel is getting us to question our position, how we view art from other cultures in the western world. The way the objects are displayed in the museum could change the way that object is viewed, even if the object’s purpose was to be part of a display. When it is removed from its natural setting it is perceived differently when placed into an artificial environment, according to Vogel “In their original setting most works of art were literally viewed differently from the way we see them”. It could also be argued the significance of the object to the culture it comes from is diminished for the people who hail from that culture when it is placed in an artificial environment, so the object loses any significance at all. It may be viewed as a tool, and the net is just that, when it is viewed in a gallery without knowledge of its people or its ritual usage. When viewed in the gallery all tribal objects have a function above form but in western society form is the most important factor. Within the African culture different objects hold higher significance to certain groups and the most highly decorated is not necessary the most highly regarded. Also in many African cultures they do not have a word for art. The language relates to an object’s usage than artistic or aesthetic value. The objects themselves are objects that the western world have decided have a greater value or more significance than others. Lt.-General Pitt, a key figure in the development of archaeology and evolutionary anthropology, donated his collection of eighteen thousand objects to Oxford University. The collection now contains half a million objects which were gifted by anthropologists and explorers. These philanthropists of the time shaped the collections to their taste and order of importance; so although these artefacts are from other cultures they are still what the western world perceived to be of significance. It could be argued that how we view art/artifacts and the cultural differences of colonialism could have impacted on how the object is viewed from the western perspective in regards to art from other cultures. What we have to examine is whether Vogel’s argument is valid and through the recontextulising of the object it breaks down these barriers. According to Areen R, (Our Bauhaus Others Mudhouse), “The distinction between the modern and the traditional is now really false, because it is the result of a historical force that is dominant today. If we wish to challenge this distinction, then it will have to be done within a context that challenges the dominance of Western culture.” It could be said that in the Art/Artifact exhibition Susan Vogal is trying to challenge this dominance by setting the object within the context of the gallery. Museums tend to use the cultural objects as bits of a puzzle which are put together in a display which are usually organized into categories to study the society and culture they belong to, whereas, in the art, this is reversed. Specifics about the cultural setting is used to appreciate the artwork and in this way the object becomes uniquely distinct from the artefact on display in the museum and one could argue that it is this uniqueness that makes it a piece of art. Furthermore, it could be said of the object that carries its own memory and communicates this through what it is and was used for. At the beginning of the 20th Century attitudes about African art began to change; no longer were the artefacts just trophies from our 19th century colonial past, but they started to be seen for their aesthetic value and African artefacts were presented alongside modernist works. In an exhibition held at 291 in 1915 African art was presented along with art by Picasso and Braque. In the exhibition the artworks were positioned to force the viewer to make associations between western and African art and it forced the viewer to make judgements about the aesthetic value of the African objects when juxtaposed to the western modernist art. Picasso later made a comment on African art, he stated “My greatest artistic emotions were aroused when the sublime beauty of the sculptures created by anonymous artists of Africa was revealed to me. These religious works of art which are both impassioned and rigorously logical are the beautiful products of all the human imagination”. Picasso is trying to get us to look at these sculptures as spiritual and other worldly and view the sculptures with a mystic romanticism. This creates a divide between the African works and Modernist pieces. This is not to say that these artists were not influenced by African art because their artwork clearly reflects those influences. The Musée du Quai is a museum which tackles the issue of colonialism and how we view cultural objects. It presents ethnographic collections. The people organisers of the exhibits described the artwork of these cultures as “arts premiers” meaning first arts as a way of trying to elevate the way the artwork from civilisations such as Africa, Asia, Oceania and the Americas is perceived by the western world. The previous name for art pertaining to this genre was “primitive art.” Jacques Chirac stated in a speech for the opening of the museum "the first peoples possess a wealth of knowledge, culture and history. They are the custodians of ancestral wisdom, of refined imagination, filled with wonderful myths, and of high artistic expression whose masterpieces rival the finest examples of Western art”. The museum has stories told by the indigenous people giving a name to people from such cultures who often remain nameless and faceless in most museums. The architecture and layout of the museum is also non-traditional; foliage in and outside the museum takes away from the harshness and imposing aesthetic that a lot of museums have which scream of empire and colonialism. Instead the use of plants and foliage creates an aesthetic poetry that flows to link the exhibits with the building. The exhibits are situated out of cases and on curved platforms, helping to create a softer and friendlier feel to the museum. It would seem although the museum takes an altruistic stance and the curators acknowledge the role of colonialism, it cannot escape the western viewpoint especially when the artworks are in a museum rather than an art gallery, surely to be viewed as art and not as something separate then these artworks must be viewed within the same parameters. Claude Levi Straus wrote an essay concerning the art of peoples from Asia and America called: Split Representation in the Art of Asia and America, in this essay he recognises prescribed parallels between art unrelated in any given time period or location with this discovery. Strauss theorises that human thought could be universal. If Strauss’ theory is right, then artwork by indigenous people does not need to separated out from other artwork and belongs in the Louvre as Jacques Chirac stated. Artists have challenged the role museums take when exhibiting artwork. James Luna is a performance artist who lives on Jolla Reservation in San Diego. He draws attention to the way artifacts and artwork of Native American and extinct societies is displayed, often romanticised and belittled within western culture. His artwork relates to his own experiences and observations. In Artifact Piece he is lying in a glass case filled with sand. There are signs surrounding him pertaining to his body, scars, name and life history. In the performance the artists Guillermo Gomez-Pena and Coco Fusco portrayed themselves as two American Indians who were from an island in the Gulf of Mexico which had remained undiscovered for five hundred years. They called the imagery island they hailed from Guatinau and called themselves Guatinauls. They were caged and beside the cage were two officials who would perform tasks such as feeding the couple and taking them to the bathroom. This involved attaching a chain to the collar around their neck. The officials would also answer questions from the public regarding the couple. The couple themselves would perform tasks such as making voodoo dolls, watching television, posing with visitors and performing a traditional dance to rap music for which they would charge. This is clearly a performance to make us question our role in western society as a subjugating force and the impact colonialism has made on other cultures. According to the endgenocide website the population of native Americans fell from an estimated 10 million+ when European explorers first arrived in the 15th century to less than 300,000 around 1900. Rising again to 5.2 million American Indian or Alaska Native in the 2010 census. The picture of the artists posing with the woman brings to mind colonial photos of people posing with indigenous people. The artists who performed this work were successful in bringing these issues to the fore and makes one question the way we view other cultures and handle the exhibiting and viewing of artifacts and their art. It could be argued that we still exploit these peoples as we did before. In the early part of the 20th century the British Colonialists were responsible for evicting Masai people from their land and this, in combination with disease and civil war, meant the population numbers dwindled to 0.5% of the original population. Today the Masai tribesmen are perceived as acquisitive by conservationists but this is not the case and the Masai are just trying to keep hold of land that is rightfully theirs. They are the indigenous people of the Masai Mara. It is no secret that places such as the British Museum acquired a lot of the artefacts whilst displacing the native people because of the colonisation of many countries when the British Empire was going strong. An exhibition opened recently at the Tate Britain called Artist and Empire (Facing Britain’s Imperial past). The exhibition is trying to provoke us into confronting the violent history which formed the British empire which some museums would rather not mention. Journalist George Monbiot notably said on this subject “The myths of empire are so well-established that we appear to blot out countervailing stories even as they are told”. It is a step in the right direction but some critics have said it does not go far enough. Deana Heath, Senior Lecturer in Indian and Colonial History, University of Liverpool “While it reveals the provenance of stolen or looted objects and images, it contains few visual representations of violence. Such images do exist, but they aren’t featured here.” With the changing attitudes to the way in which artwork from other cultures is perceived it could be said that curators are more sensitive in the way artefacts are presented. However, I do feel we have a long way to go before we get it right. One solution would be to consult with the artists who made the artwork to negotiate the best way in which to present them. In the case of artefacts where the author is anonymous it could be approached in such a way as to include its usage and cultural significance its therefore giving the object an identity as one that pertains to its culture instead of an individual. Susan Vogel was successful in that her exhibition forced the viewer into thinking about what they were looking at. I think there is a need to include the violent history behind how artefacts were acquired. Colonialism and issues of authorship should be addressed when exhibiting these objects. Although the exhibition at The Tate Britain “Artist and Empire (Facing Britain’s Imperial past)” tried to address this, it was accused of navigating away from this as there are artworks that refer to this directly. I would argue that any exhibition that contains cultural objects opens itself up to criticism and this is where the problem lies. Bibliography: (n.d.).Retrieved from www.humanityinaction.org/knowledgebase/200-the-opening-of-the-musee-du-quai-branly-valuing-displaying-the-other-in-post-colonial-france. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://endgenocide.org/learn/past-genocides/native-americans/. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://beautifultrouble.org/case/the-couple-in-the-cage/. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://isites.harvard.edu/fs/docs/icb.topic1037816.files/Readings/Feb%201st%20Readings/Levi-Strauss.pdf. (n.d.). Retrieved from forbes.com. www.richardlander.org.uk/benin_bronzes.html. (n.d.). Buddensieg, P. W. (2007). contemporary Art and the Museum. (P. w. Buddensieg, Ed.) Ostfildern, Germany: Hatje Cantz. Gamma, A. L. (2007). Eternal Ancestors. Yale University Press. https://theconversation.com/museums-have-long-overlooked-the-violence-of-empire-51269. (n.d.). Vogel, S. (1988). ART/artifact. New York: Center for African Art. www.afrikanet.info/menu/kultur/datum/2009/08/22/return-of-looted-objects-and-the-nature-of-african-leadership-part-1. (n.d.). www.allart.org/history182.html. (n.d.). www.australiacouncil.gov.au/news/media-centre/speeches/opening-of-the-musee-du-qaui-branly. (n.d.). www.khanacademy.org/partner-content/british-museum/africa1/benin-bm/a/benin-and-the-. (n.d.). www.theguardian.com/society/2016/jan/04/junior-doctors-to-strike-next-tuesday-after-talks-with-government-break-down. (n.d.). |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed